Yellow Days (2009-Ongoing)

View Point Blue (2019-2023)

series Moon and Light (2017-2019)

Kooni on Air <Chapter 1. Picnic> (2017)

Line 1 (2013-2016)

No Surprises (2016)

Ki Hyongdo (2015)

Sync Reset (2015)

Black Night (2014-2015)

Mise en Scène (2009-2013)

Concrete Romance (2013)

White Ghost Island Project (2013-2014)

Report of Subjectivity. Red Nation (2012)

series Aesthetic Surgery (2011-2017)

View Point Blue

Photography Installation

Preliminary Notes for View Point Blue

View Point Blue

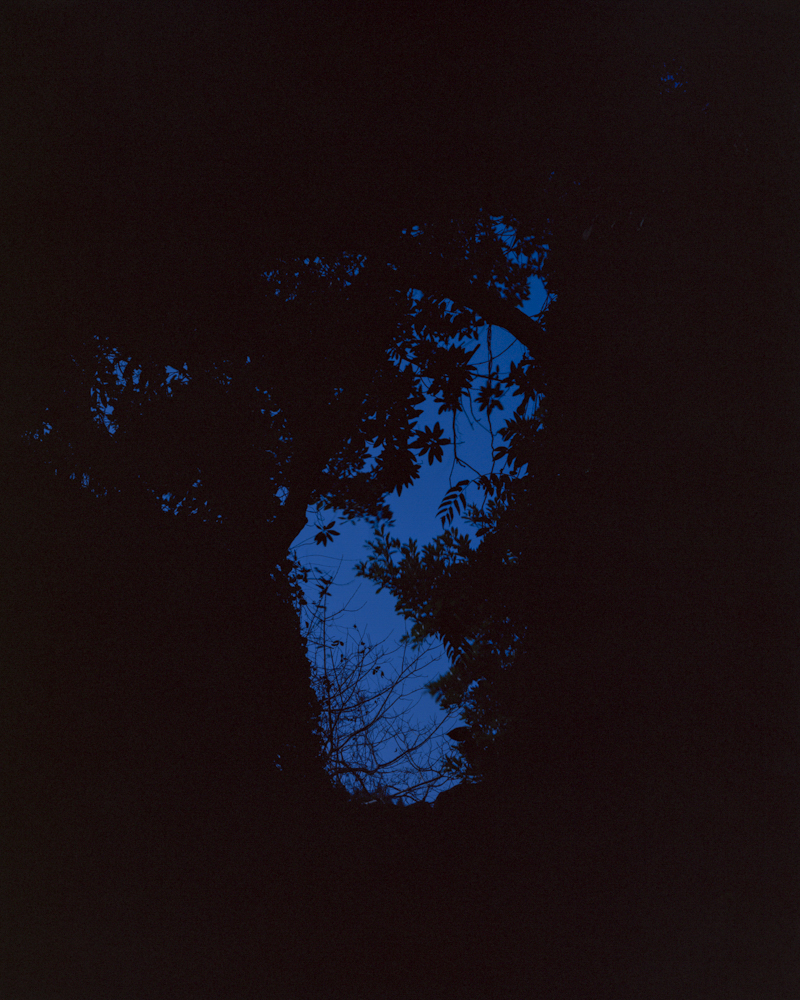

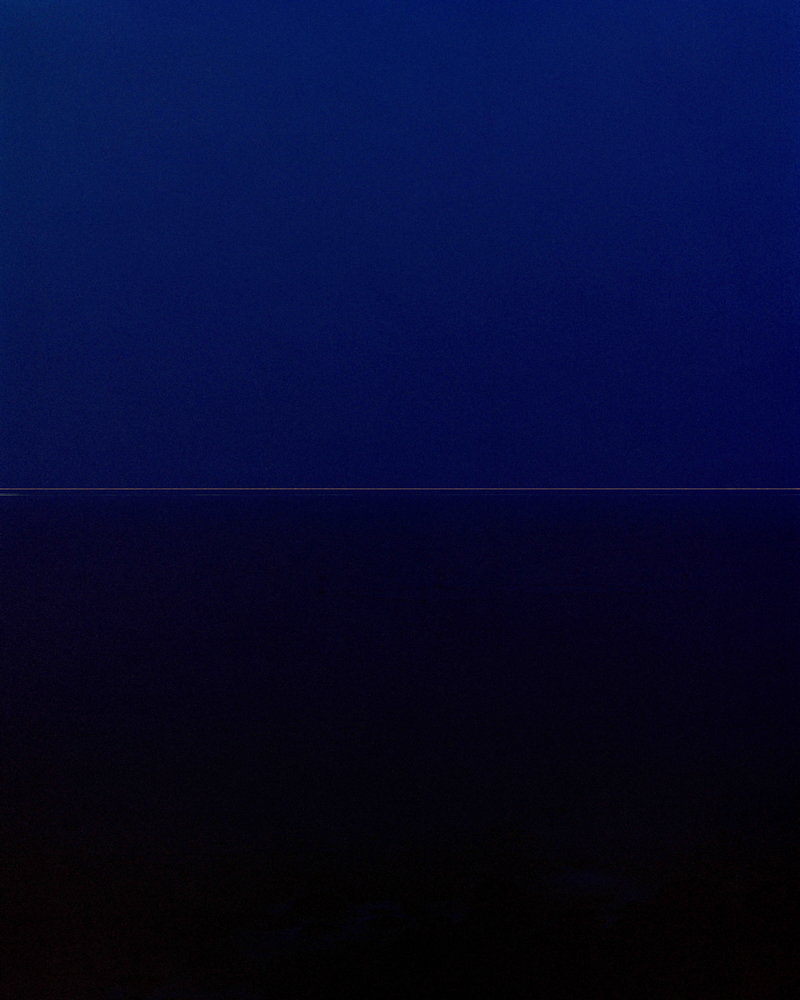

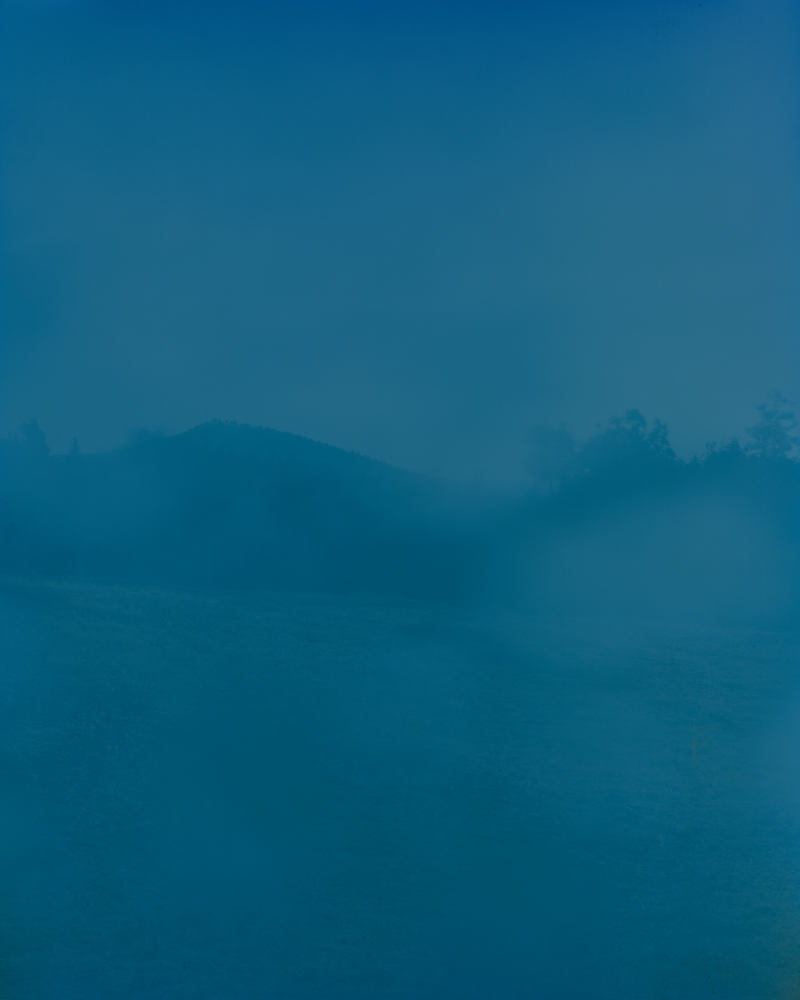

View Point Blue is a twelve-hour long-exposure photograph, made from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., attempting to reconstruct the last view seen by the victims of the Jeju April 3rd Massacre (4·3 Incident). Those who die under “favorable circumstances” often look upward—toward a ceiling or sky—when they breathe their last. Others, however, have not been given that luxury. To die while one’s gaze is fixed horizontally on the world is tragedy itself. For them, the landscape at that final moment could not have appeared as a mental image or a locus for contemplation. It would have been nothing more than the surface of nature imprinted on the retina. When landscape disappears in this way, the photograph taken at that moment escapes the category of consumable “landscape photography.” What remains is a purely literal photograph—an indexical surface of geological matter. Many of the sites chosen for executions, often for the convenience of corpse disposal, are still popular tourist spots: coastal cliffs or narrow sea passages between bizarrely shaped rocks.

Spectral Images

The deeper one searches for historical records on the 4·3 Incident, the more one encounters a layering of black-and-white photographs. Images of people with makeshift cloths tied around their heads, descending Mount Halla, accumulate like strata, forming a montage of the massacre. Behind the camera was an observer who turned the people left on the faded photographic paper into spectral images. Those who held cameras—belonging to the high social classes—exercised the authority of record-keepers as they pointed their lenses. Passing through the early twentieth century, these figures are transformed into sepia-toned ghosts, unable to show us the colors their eyes once saw.

Orange Masking

Black-and-white negative film—long favored in documentary photography—served as a witness, a liar, and a spectator to the transformations of society, becoming a witness to modernity itself. Human vision, of course, has never perceived the world in monochrome, yet photography persistently extended the limits of its own restriction. The light and color seen by those who could only roam at night seemed better suited to black-and-white images. The moon and sun, night and day, form the backdrop that makes place and time legible. In View Point Blue, Jeju becomes a darkroom, the moon an enlarger, revealing latent images of humanity itself. For some, only the blue hour and monochromatic light were visible. Color negative film uniquely includes an orange mask—reddish in appearance—added to its transparent base to minimize unwanted dye absorption and to correct color reproduction on photographic paper. The subject’s colors and the reproduction on the film exist in complementary relation. In View Point Blue, when the color temperature of dawn grows higher, the celluloid turns more yellow; the darker the exposure, the more transparent it becomes, and the brighter the exposure, the denser and blacker it reverses, forming dye clouds.

Viewpoint

In View Point Blue, the direction of the lens aligns not with the scene of the event but with a perspective never before realized in photographic history: the point of view of the subject itself. The privileged point of view constructed by documentary photography is reversed. The positions of subject and observer collapse into one another, overturning attributes, positions, directions, actions, and opinions. The moment the vantage point shifts, this reversal repeats itself throughout the work. The victim’s retina, the chemical process of film development, the print shop technician’s color couplers rendering chromogenic color, and the camera’s lonely act of seeing over twelve hours of darkness—all overlap to create an image that seeks to synchronize light with color. Standing before the resulting blue image, the present-day viewer inevitably brings their own subjectivity and reflections, shaped by the circumstances of their own position in time.

《푸른 날》을 위한 일차적 주석

푸른 날

<푸른 날>은 저녁 6시부터 아침 6시까지 4.3사건의 희생자들이 마지막으로 본 풍경을 유추해 찍은 12시간짜리 장노출 사진이다. 인간이라면 대개 형편이 좋으면 천장이나 하늘을 보고 죽는다. 반면 그렇지 않은 사람들도 늘 있었다. 어딘가를 수평적으로 바라보며 죽는 자리는 비극이었다. 그때 풍경은 사유할 수 있는 심상적 이미지의 전초인 풍경으로서 나타나지 않고 단지 망막에 맺힌 자연의 겉모습에 지나지 않았을 것이다. 풍경이 없어지는 순간, 그 순간을 찍은 사진은 소비재로 전락한 ‘풍경사진’의 카테고리에서 자유롭게 떨어져 나가 어떠한 지질 덩어리의 표피로만 남은 순수한 자연물이 찍힌 즉물 사진이다. 시체를 처리하기 편리해서 선택된 곳은 지금도 관광객들이 많이 찾는 해안가 절벽이나 기괴한 괴암들 사이의 물길이었다.

유령 이미지

4.3과 관련된 역사적 사료를 찾아 불수록 흑백사진에 대한 이미지들만 쌓인다. 마구잡이로 헝겊을 귀에 감싼 사람들이 한라산을 내려오는 이미지와 같은 사진들이 수많은 레이어를 만들어 4.3에 대한 몽타주를 만든다. 색이 바랜 인화지에 남아 있는 사람을 유령 이미지로 만든 카메라 뒤에 숨은 관찰자가 있다. 카메라를 쥔 하이클라스의 사람들은 기록자의 권위에 군림하며 렌즈를 들이댄다. 20세기 초를 통과한 사람들은 점점 세피아톤으로 변해가는 흑백 유령들로 변신한다. 그들의 눈이 본 컬러를 볼 수 없다.

오렌지 마스킹(orange masking)

다큐멘터리 사진에서 주로 이용해 온 흑백 네거티브 필름은 오랜 기간 동안 사회의 변화상을 기록하는 증언자이자 거짓말쟁이이자 관람자로 근대의 목격자였다. 사람의 눈은 한 번도 흑백으로 본 적이 없지만 사진은 잘도 자신이 가진 한계를 밀어붙였다. 밤 시간대만 돌아다녔던 사람이 본 빛과 색은 흑백사진에 더 적합해 보인다. 달과 태양, 밤과 낮이 장소와 시간을 형성하는 배경은 확대기인 달과 암실인 제주도라는 공간이 특정한 사건으로 드러나는 잠상적 이미지로서의 우리 인간의 모습이 나타난 때이자 누군가에게 푸른 시간의 빛과 단일색만이 드러났던 카메라 옵스쿠라다. 컬러 네거티브 필름에만 있는 오렌지 마스킹은 붉은색을 띤다. 인화지상에 드러나는 부정색소(不正色素)를 최소화하기 위해 무색투명한 필름 베이스에 오렌지 마스킹을 한다. 컬러 네거티브 필름의 피사체의 색과 필름상의 재현색은 서로 보색관계에 있다. 그래서 <푸른 날>에서 새벽녘의 색온도가 높으면 셀룰로이드는 더욱 노랗게, 어두울수록 투명하게, 밝을수록 검게 반전되어 다이 클라우드(dye clouds)를 만들어 낸다.

뷰 포인트

<푸른 날>에서 렌즈가 향하는 방향은 사건 현장이 아니라 사진의 역사에서 단 한 번도 실현된 적 없었던 피사체의 시선과 겹친다. 다큐멘터리 사진이 구축한 시점이 리버스샷으로 전환된다. 반대편에 놓였던 것들이 서로의 입장을 전복시킨다. 속성, 위치, 방향, 행동, 의견이 뒤틀리고 시점이 바뀌는 순간이 <푸른 날>에서 반복된다. 피해자가 가진 망막, 사진 제작 일반의 현상과 스캔, 인화를 담당하는 프린트샵 실장님의 유색 커플러(color coupler)로 변환된 발색감, 그리고 12시간 동안 죽음과 추위만이 감도는 어둠에서 카메라만이 보고 있는 무엇과 사람들의 체온을 느끼기 위해 호시탐탐 노리는 촬영자의 프레임화 된 눈. 각 시점들은 일치될 수 없는 이미지를 겹치며 하나의 색과 상을 얻기 위해 빛을 색으로 동기화하려 노력한다. 이 푸른 빛이 조성한 사진 이미지 앞에 선 구경꾼이자 관람객이 현재의 시점에서 각자의 처지에 따라 다른 생각을 하는 것은 자연스러운 일이다.